- Regular Bars $6.95

- ✱ Premium Bars $8.95

- Almond Aloe

- ✱ Almond Green Tea

- ✱ Almond Spice

- Avocado Lemon

- Balsam Fir & Juniper

- ✱ Bay Rum

- Biotherapy Black

- Biotherapy Skincare

- Black Forest Chamomile

- Brown Windsor

- Camper's Choice

- Cedar Cypress

- ✱ Chai Spice

- ✱ Chocolate

- Citrus Oatmeal

- Eucalyptus Mint

- Evergreen

- Fennel Mint

- ✱✱ Frankincense & Myrrh

- French Lavender

- Gardener's Hand Soap

- Ginger Neem

- ✱ Indonesian Safflower

- Island Spice

- Italian Bergamot

- LaRee's Scent Free

- Lavender Licorice

- Lavender Oatmeal

- Licorice

- Lime Coconut Aloe

- May Chang

- Meteor Showers

- Mojito

- Natural Citronella & Marigold

- Old-Fashioned Lye

- ✱ Patchouli Hemp Seed Oil

- Patchouli Orange

- Peppermint

- Pink Grapefruit

- Pink Grapefruit Eucalyptus

- Pompeii Pumice

- Rose Geranium

- Rosemary

- Rosemary Mint

- Rosy Bouquet

- Saffron Gold

- Sage Lemongrass

- Sassafras Birch

- Sea Spice

- Shaw's Garden

- Silver Fir & Lavender

- Sink Side Kitchen Soap

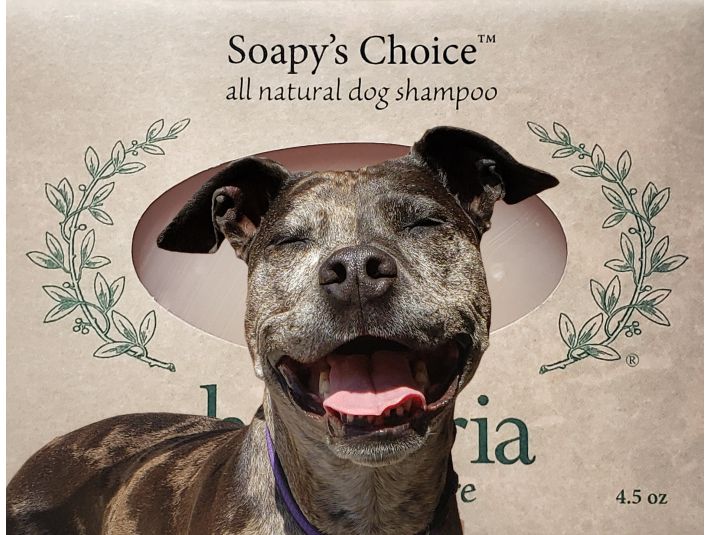

- Soapy's Choice

- Spearmint Orange

- Sugandha Kokila & Laurel

- Sweet Orange & Vanilla

- Tea Tree Green Tea

- Tomato Surprise

- Traveler's Choice

- Triple Mint Oatmeal

- Tutti Frutti

- Vanilla

- ✱ Vetiver Walnut

Husband and Wife's Chemistry led to Sweet-Smelling Soap Empire

By Pamela Selbert

SPECIAL TO THE POST-DISPATCH 03/03/2006

The delicate fragrance that wafts from inside the house is nearly as welcoming as Ken Gilberg, soap maker, as he opens the door to visitors and extends a hand in greeting. He smiles at a comment about the delightful aroma, and says, "You'd never know four cats live here, would you?" Well, no, except for the fact that at least a couple of members of the quartet, all foundlings, he says, are always on hand, gliding around furniture and feet. And, anyway, cats that sit on a company's "board of directors," as Gilberg jokes these do, are probably too sophisticated to use a litterbox.

The delicate fragrance that wafts from inside the house is nearly as welcoming as Ken Gilberg, soap maker, as he opens the door to visitors and extends a hand in greeting. He smiles at a comment about the delightful aroma, and says, "You'd never know four cats live here, would you?" Well, no, except for the fact that at least a couple of members of the quartet, all foundlings, he says, are always on hand, gliding around furniture and feet. And, anyway, cats that sit on a company's "board of directors," as Gilberg jokes these do, are probably too sophisticated to use a litterbox.

Gilberg explains that the lovely smell is coming from his lower-level workshop, where he has just finished mixing up a batch of soap - on this occasion a type he calls Black Forest Chamomile. It combines the "traditional scents of Germany, bergamot, cinnamon, lavender, lemongrass and orange," he says. No wonder the house smells so good.

But this is just one of the two dozen varieties Gilberg makes of a product he calls Herbaria Soaps. Others go by such appealing names as Indonesian Safflower, Island Spice, Lavender Cobblestone, Sage Lemongrass and Sea Spice. There's even one called Pennyroyal Pet Soap, which is lightly scented with mint, and may be intended for fur, but can be enjoyed equally by the pet's guardian, Gilberg says. The soaps are "loaded with oils, all plant-based, and totally natural, no artificial ingredients," he adds.

Gilberg, 55, was a professional photographer and graphic designer until about three years ago, when he began making and marketing his soaps, of which he sells some 15,000 bars a year. It all started when his wife of seven years, LaRee DeFreece, an attorney, was considering a career in patent law, studied chemistry for the work, and "became excited about molecules," he says.

"She came up with the recipes, and they are still hers," he says. "Herbaria soaps aren't detergent like most soaps, and contain no additives or synthetic coloring. What they are is extremely moisturizing, good for the skin." Recently juried into the Best of Missouri Hands, Herbaria soaps are "made the old-fashioned way," he adds.

Initially Gilberg and his wife made soap "till all hours" in their kitchen in Kirkwood. But after it was available at a Best of Missouri show at the Missouri Botanical Garden, where "people went nuts for it," Gilberg decided that soap making would be his career, and created a proper workshop in his home.

Initially Gilberg and his wife made soap "till all hours" in their kitchen in Kirkwood. But after it was available at a Best of Missouri show at the Missouri Botanical Garden, where "people went nuts for it," Gilberg decided that soap making would be his career, and created a proper workshop in his home.

On a recent occasion he offered to demonstrate the soap-making process, and led the way to the workshop (no cats allowed), where dozens of shelves contain trays of bars that are "curing," waiting to be packaged, and hundreds of boxes of wrapped bars awaiting purchase or shipping. Gilberg notes that he can make up to 600 bars a day.

The source of the fragrance we had smelled upstairs is a 12-inch cube of soap, just poured into a stout plastic-lumber container. Gilberg explains that when it's good and solid, after about two days, he will slice it (using a device outfitted with guitar strings, that looks like a giant egg slicer) into 15 logs. These logs, in turn, will each be cut into 11 bars.

Gilberg designed the paper wrappers, which list ingredients and benefits. He also took the photo of Nugget, the couple's longhaired white cat, which appears on boxes of the soap with a "thank you" for the order. (Scroll  down the Herbaria Web site — www.herbariasoap.com — to read dozens of comments from well-pleased customers from all over the U.S. and several other countries.)

down the Herbaria Web site — www.herbariasoap.com — to read dozens of comments from well-pleased customers from all over the U.S. and several other countries.)

Gilberg's workshop includes a large jacketed heater that looks like an open-top water heater, but was actually designed to heat honey to prevent it from crystallizing. It is set at 104 degrees, and contains a yellow, pudding-like mix of oils: soy (30 percent), palm kernel (30 percent) and olive (40 percent). Nearby are shelves that hold jars of the oils, also brown glass bottles and larger steel cans of the 20 essential oils that scent the soap, among them peppermint, rosemary, tangerine, tea tree, rosewood, laurel berry, catnip (an excellent insect repellent, says Gilberg) and bergamot. The steel-top worktable is outfitted with a two-burner heater for warming the mix of lye and water (he combines them outside for safety) that will cause the oil to "saponify" or thicken to become soap.

A "batch" of soap includes about 37 pounds of warm oil (he drains the amount through a spigot into a large stainless steel pot). To this he adds the lye mixture (five pounds of lye to 13 pounds of water; Gilberg prefers working in pounds rather than ounces) and stirs it using a "squirrel-cage" mixer attached to an electric drill. (If crushed dried flowers, herbs or oatmeal are to be included, they are poured in along with the lye and water.) After just a few minutes, when the concoction has begun to saponify, he adds about one cup of "super-fatty agent," which on this occasion is shea butter, though he also could use oil from hempseed, jojoba or avocado. Finally he stirs in whatever essential oil - or combination of oils - the soap will include, and pours the mix into another plastic-lumber mold standing on a wood frame nearby on the floor. He jostles the mold to eliminate any air bubbles, then covers the soap with a sheet of plastic wrap, where it will cure for at least 48 hours before being cut into bars.

A "batch" of soap includes about 37 pounds of warm oil (he drains the amount through a spigot into a large stainless steel pot). To this he adds the lye mixture (five pounds of lye to 13 pounds of water; Gilberg prefers working in pounds rather than ounces) and stirs it using a "squirrel-cage" mixer attached to an electric drill. (If crushed dried flowers, herbs or oatmeal are to be included, they are poured in along with the lye and water.) After just a few minutes, when the concoction has begun to saponify, he adds about one cup of "super-fatty agent," which on this occasion is shea butter, though he also could use oil from hempseed, jojoba or avocado. Finally he stirs in whatever essential oil - or combination of oils - the soap will include, and pours the mix into another plastic-lumber mold standing on a wood frame nearby on the floor. He jostles the mold to eliminate any air bubbles, then covers the soap with a sheet of plastic wrap, where it will cure for at least 48 hours before being cut into bars.

Because the soap is made the "old-fashioned way," as it could have been done a century and more ago, it is available at a number of such appropriate sites as the gift shops at the Missouri History Museum, Gateway Arch and Missouri Botanical Garden, and at Global Food Market. It can also be purchased at the baths in Hot Springs, Ark.; at fairs such as the Festival of the Little Hills in St. Charles; and, of course, by contacting Gilberg.

Because the soap is made the "old-fashioned way," as it could have been done a century and more ago, it is available at a number of such appropriate sites as the gift shops at the Missouri History Museum, Gateway Arch and Missouri Botanical Garden, and at Global Food Market. It can also be purchased at the baths in Hot Springs, Ark.; at fairs such as the Festival of the Little Hills in St. Charles; and, of course, by contacting Gilberg.

"I love making it, love that it's something my wife and I can do together," he says with a smile. "I find the work very exciting - and feel like the luckiest man in the world."

For a list of Herbaria Soaps and gift sets or to place an order, call Ken Gilberg at 314-822-4092 or go online to www.herbariasoap.com.

Burano Laundry Soap

Burano Laundry Soap